In 2014, at the APEC summit, Xi Jinping pledged that China would rely more on domestic demand and reduce its dependence on exports. In his own words, China’s economy should “更多依赖国内消费需求拉动,避免依赖出口的外部风险”, rendered in the official English version of the speech as “the Chinese economy is being driven increasingly by domestic consumer demand, thus avoiding external risks from an overreliance on exports.”

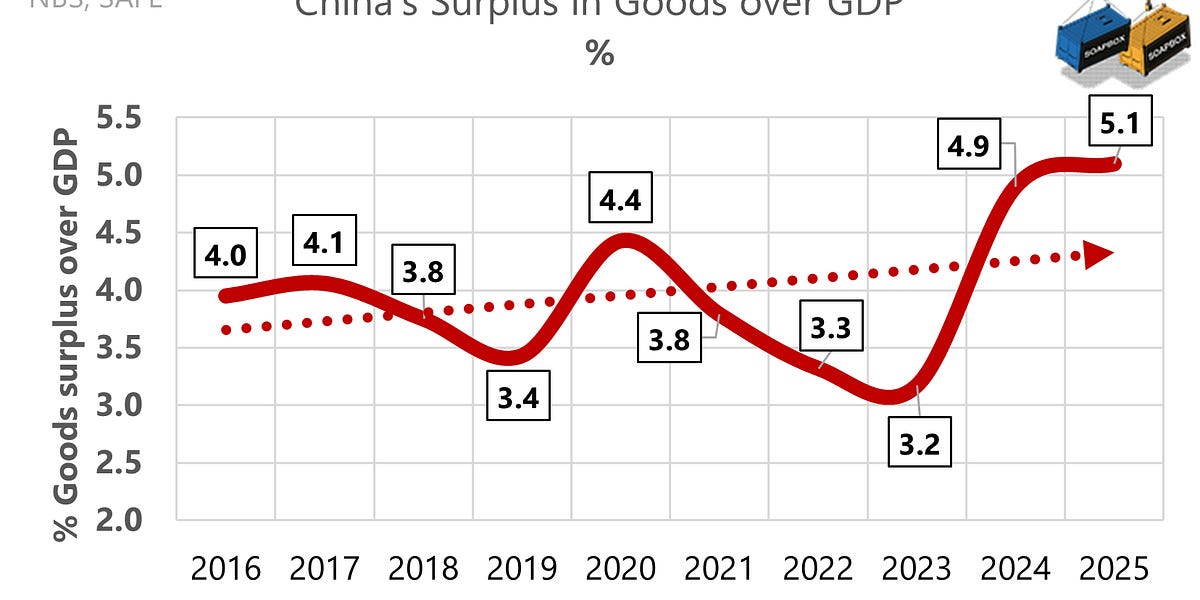

A decade later, the numbers show the opposite: China’s growth is once again underpinned by an unusually large goods surplus.

Note that we use SAFE data for the goods surplus. If instead we used Chinese customs data, the surplus as a share of GDP would be even higher. The large gap between the customs and SAFE series is striking and, so far, has never been fully explained

Note that we use SAFE data for the goods surplus. If instead we used Chinese customs data, the surplus as a share of GDP would be even higher. The large gap between the customs and SAFE series is striking and, so far, has never been fully explained

On paper, the economy grew by 5.2% in real terms in the first three quarters. Yet fiscal revenue rose by only 0.8% in nominal terms. Part of this gap is mechanical: prices are falling and the authorities are still giving back revenue through tax cuts and export rebates. Part reflects the shift away from property and big-ticket consumption, which used to be reliable cash cows for the budget. And part may simply suggest that underlying growth is weaker than the headline GDP figures imply.

It is also worth noting that personal income tax accounts for only about 7% of total tax receipts in China, compared with roughly a quarter in most advanced economies.

Additionally, the 6.2% rise in cultivated land occupation tax is awkward for China’s narrative: this levy is paid when farmland is converted to construction or industrial, so higher revenue points to more land being taken out of cultivation even as the government insists it is protecting and expanding arable land.

-

VAT 4% growth for the biggest broad-based tax is modest vs official real GDP (5.2%), suggesting weak domestic demand and low prices rather than a booming economy

-

Corporate Income Tax roughly tracks company profits; +1.9% growth implies profits are basically flat in real terms, consistent with pressure on firms despite headline GDP growth

-

Import VAT falling taxes here point to weak imports (-1%) and lower commodity prices

-

Excises and luxury items, +2.4% is weak and fits with subdued household spending

If you are curious, the working hours reported by the National Bureau of Statistics, and therefore by the Chinese government, measure actual working time excluding lunch breaks. Official documents make no judgement about whether these hours are “too high”. They treat the figure as a neutral indicator.

China’s economic media does notice the trend. Articles state plainly that overtime is widespread and getting worse, and they acknowledge that labour law is not being enforced, but they largely avoid direct criticism. They also stress that flexible workers such as couriers, food-delivery riders and ride-hailing drivers are not included in the enterprise-employee statistics, so the true average for the whole workforce is likely even higher.

Among netizens, anecdotal evidence points to resignation. A few, however, warn that in export markets these long hours could become a liability for China’s exports to advanced economies.

After Western automakers pulled out of Russia in 2022 following its invasion of Ukraine, Chinese brands stepped in and now control over half the market.

Yet Russian policies such as higher import duties have slowed Chinese exports, hinting that this “unlimited friendship” may not be so unlimited after all.

The Christmas-item export season is over: while export volumes are down 1%, the FOB price per unit of volume has fallen by 11% in both yuan and U.S. dollars. This is not a major item in China’s export portfolio, but it is a useful gauge of current trends in China’s mass-market export manufacturing sector. This year, the value of exports in this segment will be about one-third lower than three years ago, even though volumes are broadly similar

After the United States scrapped its de minimis import limit, Shein, Temu, AliExpress and other platforms quickly redirected their flood of cheap parcels towards the EU and the UK. A similar move is expected in the EU soon, removing the €150 duty-free threshold and likely adding a fixed fee per parcel. The trade diversion is already visible: in 2025, export volumes to the EU are up by more than 50%.

China’s exports are more labour-intensive than the EU’s: for the same export value, many more workers are employed in China than in the EU. This is consistent with higher capital intensity, higher wages and a more knowledge-intensive export mix in the EU.

It also means that a given change in external demand has a larger employment impact in China than in the EU.

Recent pieces in The Economist and the South China Morning Post say Germany is on track to run a $100bn (about €87bn) trade deficit with China in 2025. Yet SOAPBOX readers may have seen a very different figure: from January to September, Eurostat data show a German deficit with China of just €15.2bn. The gap between these numbers is large enough to demand an explanation and the reasons for it carry some political nuance.

Even if we stay at the level of pure numerology, Germany’s bilateral deficit with China looks very different depending on which statistics you use. The “$100bn (about €87bn)” projection in The Economist and the South China Morning Post is based on data from the German stats office, Destatis, and an official forecast. This approach counts all goods whose origin is China, including those that first enter the EU through ports in the Netherlands or Belgium before being shipped on to Germany.

Eurostat’s harmonised trade data, by contrast, often attributes those same flows to the country of consignment, such as the Netherlands or Belgium. As a result, Germany’s recorded imports “from China” are much smaller and the bilateral deficit is also much smaller. Both sets of numbers are internally consistent; they are simply built on different ideas of who is considered to “import” Chinese goods.

For those of us guided by Eurostat’s methodology, the figure of about €15.2bn deficit so far this year holds. This is not only about technical choices, but also about the political pillars that sustain the EU. If you calculate the deficit in the Destatis-style way used by The Economist and the SCMP, you are quietly treating the EU as if it had 27 external borders instead of one. In legal and practical terms, there is one EU customs territory and one external border with China; goods cleared in Rotterdam or Antwerp have already “entered” the EU by the time they reach Germany.

Treating national data as the natural lens for “exposure to China” risks weakening the logic of the single market and the EU’s common trade policy, because it re-nationalises what is, in fact, a shared border and a shared competence.

Spain has reported its first case of African swine fever in thirty years. Before trade can resume, Madrid and Beijing must agree on the perimeter of the affected zone. Spain’s pork exports to China are divided about evenly between meat and offal.

The pork category is China’s second-largest import from Spain, after copper.

The value of EU imports by rail from China in the first three quarters of 2025 is down 21 percent compared with the same period in 2024. However, following China’s playbook, the drop in volume is much smaller, at just 8 percent.

The U.S has decided to keep a set of exceptions to the extra “Section 301” China tariffs in place, instead of letting them expire at the end of November. That means 178 specific Chinese products will continue to avoid the additional punitive duties and will be taxed at the normal U.S. tariff rate until 10 November 2026.

The list is narrow and mostly covers specialised industrial and medical inputs and equipment, for example certain electric motors, pump and valve components, blood-pressure monitors and other medical devices, printed circuit boards, and machinery used to manufacture solar products and batteries.

To the best of our knowledge, other than repeatedly extending a narrow set of 178 product exclusions, the Trump administration has not so far changed the underlying Section 301 China tariff lists in its second term.

We are committed to sharing with you the best trade analysis we have to offer.

If you would like to share something with us, feel free to comment in the section below or drop us a line at [email protected]

Like this:

Like Loading…

Разгледайте нашите предложения за Български трактори

Иберете от тук

Българо-китайска търговско-промишлена палата