In an economic security doctrine to be unveiled on Dec. 3, the European Commission will reassess its trade defence arsenal and decide whether stronger measures are needed to deal with China. During the visit of Germany’s Vice Chancellor Lars Klingbeil, Chinese propaganda reverted to its usual narrative, highlighting that trade between Germany and China is larger than Germany–U.S. trade while conveniently ignoring the trade balance.

While Germany recorded a surplus of €59bn with the U.S. in the first three quarters of 2025, its deficit with China ballooned to €15.2bn from virtually zero a year earlier. Reducing such an unbalanced relationship to a story of ‘mutual trade’ is not just misleading, it is deliberate.

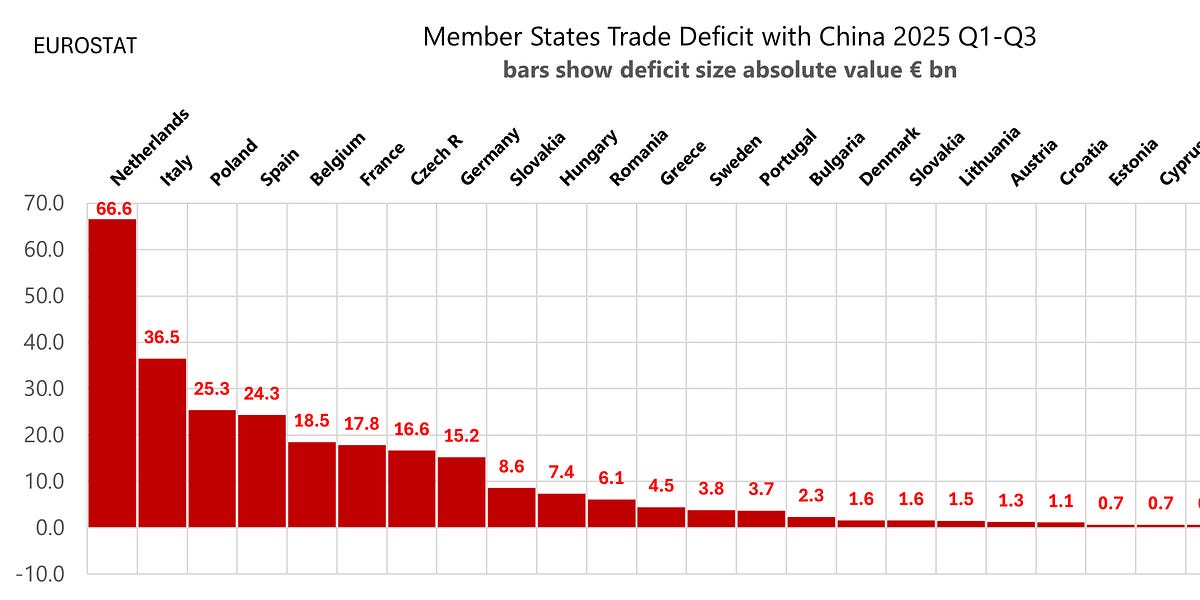

The chart shows the trade balance where Chinese goods enter or leave the EU. Keep in mind that inside the EU single market goods move freely between member states

The chart shows the trade balance where Chinese goods enter or leave the EU. Keep in mind that inside the EU single market goods move freely between member states

Jorge Toledo, the EU ambassador to China, says the EU–China relationship has not improved since the summer summit, despite Beijing’s partial one-year easing of rare earth export controls.

Toledo is pushing back against China’s habit of treating the EU as 27 separate capitals to be played off against one another, warning that if Beijing continues to underestimate the EU as a political union, it may miscalculate and trigger tougher EU responses on trade defence.

The EU’s stockpile plan for critical (especially strategic) raw materials is essentially about insurance against supply shocks and geopolitical pressure: the EU wants a new Critical Raw Materials Centre that will monitor global markets, coordinate joint purchasing by member states and industry, and build up shared European reserves.

In Brussels-speak, “minerals” is not just ores. It covers the full chain of CRM-bearing materials up to the industrial grades used in magnets, batteries and similar inputs, while magnets, motors, EVs or turbines sit on the other side of the line as applications that consume those raw materials.

Notice the Greek export boom to China in 2024–25 is off the chart. It turns out to be entirely a fuels story. Re-exports / refined fuels produced in Greece from imported crude, shipped to China when the arbitrage works.

EU imports of industrial robots from China jump 57% in 2025, compared with a 17% increase from all other suppliers. China’s share of EU industrial robot imports rises from 22% to 28% in just one year.

Imports in the first three quarters of this year are up 123% on the same period in 2024, and 2025 imports are already more than 200% above the 2019–2024 average. That kind of surge is a warning signal and often the first step towards an anti-dumping probe.

EU imports from Russia are set to fall by a further 20% in 2025 compared with a year earlier.

Since the invasion of Ukraine, China has imported more than €400 billion in goods from the Russian Federation, effectively extending a helping hand to Putin’s regime.

China has doubled its LNG imports from Russia by volume since the summer.

China has reimposed a blanket ban on Japanese seafood imports and is presiding over mass cancellations of trips to Japan, officially citing food safety and security concerns, but in practice signaling anger at Tokyo over Taiwan.

Travel warnings, withdrawn tour packages amplify the pressure on Japan’s tourism and retail sectors, turning trade and people flows into quiet tools of political retaliation.

Within hybrids, plug-ins represent 69% of import value, up from 44% over the same period in 2024.

By value, EU imports of Chinese-made electric cars are now around €3.5 billion below their peak two years ago. At typical import prices, that implies a drop of roughly 130,000–140,000 cars over two years. On top of that, Tesla now builds the higher-priced Model Y in Berlin for the European market, while imports from Shanghai are increasingly concentrated in the cheaper Model 3.

The China Chamber of Commerce to the EU (CCCEU), a Chinese business lobby, accuses the Dutch government of “banditry” over the Nexperia case, a term that is unusually strong in English and, in this context, quite offensive.

On paper, the CCCEU presents itself as a bridge-builder for Chinese companies in Europe, but in practice it mirrors the Chinese state’s trade and diplomatic agenda.

The collapse in EU imports of FAME biodiesel from China in 2025 is basically policy-driven. After a surge of cheap Chinese biodiesel flooded the EU in 2023–24, the EU imposed provisional anti-dumping duties from August 2024 and definitive duties in February 2025, explicitly covering FAME biodiesel. Once those measures took effect, Chinese shipments to the EU dried up

Qiushi, the CCP’s theoretical journal, has just published a Xi text on the economy. In section III, Xi imports the mainstream economics view that higher total factor productivity (TFP) is the key sign you’re doing something right, but he domesticates it: TFP remains an outcome and a metric, yet is framed as the measured result of consciously upgrading and recombining workers, means of labour, and objects of labour.

In doing so, Xi is trying to ideologise and re-own a concept that was originally developed to describe what market-based, decentralised systems tend to do better. He appears genuinely convinced that a top-down, Party-led system can deliver the same kind of TFP gains. A Western economist, however, would still worry that political control eventually dominates, and that TFP then suffers as misallocation and risk-aversion grow.

Nobel laureate Robert Solow’s TFP was born out of US private-sector data and competitive-market assumptions, not out of any attempt to measure the efficiency of planned economies.

Actually, a book introducing Xi Jinping’s economic thought has been published by the People’s Publishing House. According to Chinese government, the book will serve as a key textbook for students majoring in economics. Imagine.

SOAPBOX attended EU Trade Policy Day 2025 in Brussels on 20 November. The event opened with a reminder of the strategic importance of trade for the European economy: 30 million EU jobs depend on trade (see *), and 90% of the EU’s economic growth is linked to extra-EU markets

The Commission also announced the launch of the first EU–CPTPP Trade and Investment Dialogue, signalling a broadened engagement with Indo-Pacific partners.

As for the EU–MERCOSUR Agreement, its ratification continues to face delays. Our take is that these delays are linked to the fact that in 2024 the EU recorded a $50 billion trade deficit with MERCOSUR across 33 product categories. Of these, 16 categories fall under agrifood, amounting to $24 billion of the deficit, largely driven by imports of oilseeds, coffee, meat, fish and fruit. Coffee and oilseeds are structural long-term imports for Europe, while categories such as fruit, meat, fish and corn explain the domestic sensitivity in agricultural circles. At the same time, the EU maintains a $42 billion surplus across 64 product categories, bringing the overall net balance to an $8 billion deficit.

These figures provide a clearer baseline for understanding the dynamics of the negotiation: agriculture remains a relevant and sensitive component, but it is only one part of a broader, diversified trade relationship, with China’s role in the background.

China recorded a $36 billion trade deficit with the MERCOSUR bloc, but this can be misleading: the deficit is concentrated in one country alone: Brazil ($44 bn). With the rest of the bloc members, China enjoyed an $8 billion surplus.

(*) According to our estimates, the EU requires about 30 million jobs to generate €2.6 trillion in goods exports outside the EU. For China to reach the same export value, it needs just over 86 million jobs.

We are committed to sharing with you the best trade analysis we have to offer.

If you would like to share something with us, feel free to comment in the section below or drop us a line at [email protected]

Like this:

Like Loading…

Разгледайте нашите предложения за Български трактори

Иберете от тук

Българо-китайска търговско-промишлена палата