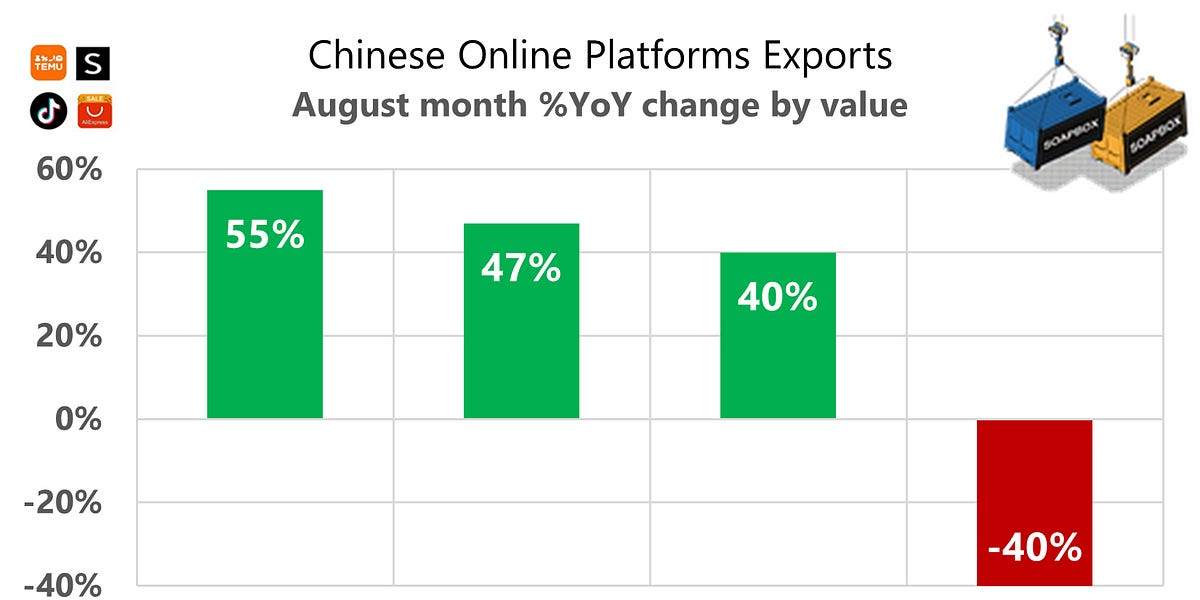

In February, when Trump signaled he would close the de minimis door that China’s platforms use to ship low-cost parcels to the U.S., we did not cheer. We sighed. Europe would inherit the deluge. In August 2025, the reroute showedup in the data: the EU up 55 percent, the UK up 47 percent, the rest of the world up 40 percent from a smaller base, not enough to offset the U.S. drop. As for the U.S., exports were down 40 percent by value.

A year earlier, a quarter of the cheap stuff consumers scroll past on AliExpress, Temu, Shein, and TikTok was headed to the U.S. The EU took 19 percent, and the UK just 3.6 percent. Together these three affluent markets absorbed 47 percent of Cheap China’s exports. That matters at home. Low-cost products are job-dense, about 60 jobs for every $1 million exported. Overall, made-in-China affordable goods from electronics to underwear account for more than 3 percent of China’s total exports. In our dataset, this is the number one export category, ahead of smartphones, electric cars, solar panels, and lithium-ion batteries.

Beijing borrows feng shui and speaks of “sitting north, facing south,” as if China can replace lost Western demand with the Global South. Not overnight. Perhaps not ever. Traders knew this. When Trump moved to close the de minimis loophole, they did the practical thing. They pivoted from the U.S. to the other two affluent markets on the map, the EU and the UK. We knew where the flood would go.

And it did.

Europe is “the only place where we don’t protect our domestic players,” he argued, urging the Commission to widen tariff action and harden reciprocity.

“If we want to remain sovereign, we have to protect the existing players when they suffer from the absence of a level playing field”

The EU is working off for the steel package first. It will halve quotas and lift the over-quota duty to 50%

With a different view, Martin Sandbu, in the FT’s Free Lunch, argues against tariffs and says he has stopped worrying about China’s surplus. He makes that case without asking whether all surpluses are comparable. They aren’t. China’s surplus is engineered by policies that suppress domestic demand and push subsidised capacity abroad; Europe’s is a by-product of more contestable markets and an open capital account. Sandbu’s proposal is to recycle China’s surplus into productive investment overseas.

The counterpoint is simple,

Recycling only works if the surplus is earned in fair competition. Otherwise you are laundering distortions.

The European Union is set to launch the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) on January 1, 2026, the world’s first large-scale border tax on carbon-intensive goods. The Chinese government labels CBAM a “unilateral measure” and says China will “actively respond.”

Fruit Attraction just wrapped in Madrid, reaffirming its place near the top of global fresh produce fairs. China has approved nearly 30 fruit import protocols with EU members, from Dutch pears to Spanish persimmons and Italian kiwifruit. Yet EU fruit exports to China are on the verge of extinction. This is not a broader slump. Extra-EU sales are thriving and Fruit Attraction is buzzing. China’s share is 0.4%, which means one euro out of every 250, practically a rounding error.

In 2021, Beijing celebrated a milestone: per-capita disposable income (PCDI) reached 32,189 yuan, roughly double the 2010 level. To repeat that feat this decade, doubling the 2020 level by 2030, the PCDI would need to grow about 8.3% a year during 2026–2030. The first half of the decade delivered about 5.5% a year. Without a sharp and lasting pick-up, the math does not work. On our estimates, 2030 lands roughly 17% short of another “doubling.”

PCDI Doubling by 2030 Slipping Out of Reach

PCDI Doubling by 2030 Slipping Out of Reach

First half of the decade in one glance, see the table above. Disposable income and spending rose at almost the same pace, about five and a half percent a year. The saving habit did not blink. Close to one-third of income is still put aside, not spent.

Five years is plenty of time for a mood change. It did not happen. Households feel the future feels foggy, so they keep buffers. The leadership in China talks up consumption but works the old levers of supply and net exports, worried about jobs. Unless that perception shifts, the caution in wallets will stay.

Five years in and the shopping cart barely changed. Food plus alcohol and tobacco is still 30% of spending, so no Engel-style upgrade. Housing stays the runner-up and the planners’ headache. Lifestyle lines don’t gain ground. Even with appliance subsidies, “household stuff” takes the same slice in 2025 as in 2021.

In the last week of September, the Shanghai–U.S. West Coast freight index based on settled rates fell by 23%. It is now below the benchmark level of 1,000 set in June 2020.

So far in 2025 the PMI employment subindex is only marginally better than in 2024

Always the same story. In October 2023 Vucic cheered the China-Serbia FTA as “a big step forward.” Two years later it’s Groundhog Day in trade. Tariffs fall, Serbia’s imports from China surge, Serbia’s export mix to China thins, and the deficit is about twice as large.

Liberia is a classic flag-of-convenience registry: shipowners anywhere can register vessels under its flag even if those ships never call at Liberia. Owners choose it for lower fees and taxes and quick paperwork. In trade data, customs often record the registry as the “destination,” which inflates the bilateral export figure. Actual goods exports to Liberia are only about 20% of China’s recorded exports to Liberia.

By January 2025, the world fleet counted 112,500 vessels. China (~20%), EU (~20%), Japan (~10%) control half of capacity, while nearly 50% of capacity is registered in just three flag states, Liberia, Panama and the Marshall Islands

On 23 September 2025, the European Union and Indonesia finalised their negotiations on the ‘Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement’ (CEPA). The EU and Indonesia will eliminate tariffs on over 98% of tariff lines, and close to 100% in terms of value. 80% will be liberalised already at entry into force, and after a 5-year phase out liberalisation will reach 96% of trade.

As of this month, the U.S. is phasing in service fees on vessels that are Chinese-owned or Chinese-built when calling at U.S. ports.

-

Chinese-owned vessels: $50 per net ton in the first phase, rising to $140 per net ton by April 2028.

-

Chinese-built vessels (any ownership): the higher of $18 per net ton or $120 per container initially, increasing to $33 per net ton or $250 per container by April 2028.

For Chinese-built vessels, operators pay whichever is higher, the per-net-ton fee or the per-container fee.

We are committed to sharing with you the best trade analysis we have to offer.

If you would like to share something with us, feel free to comment in the section below or drop us a line at [email protected]

Like this:

Like Loading…

Разгледайте нашите предложения за Български трактори

Иберете от тук

Българо-китайска търговско-промишлена палата