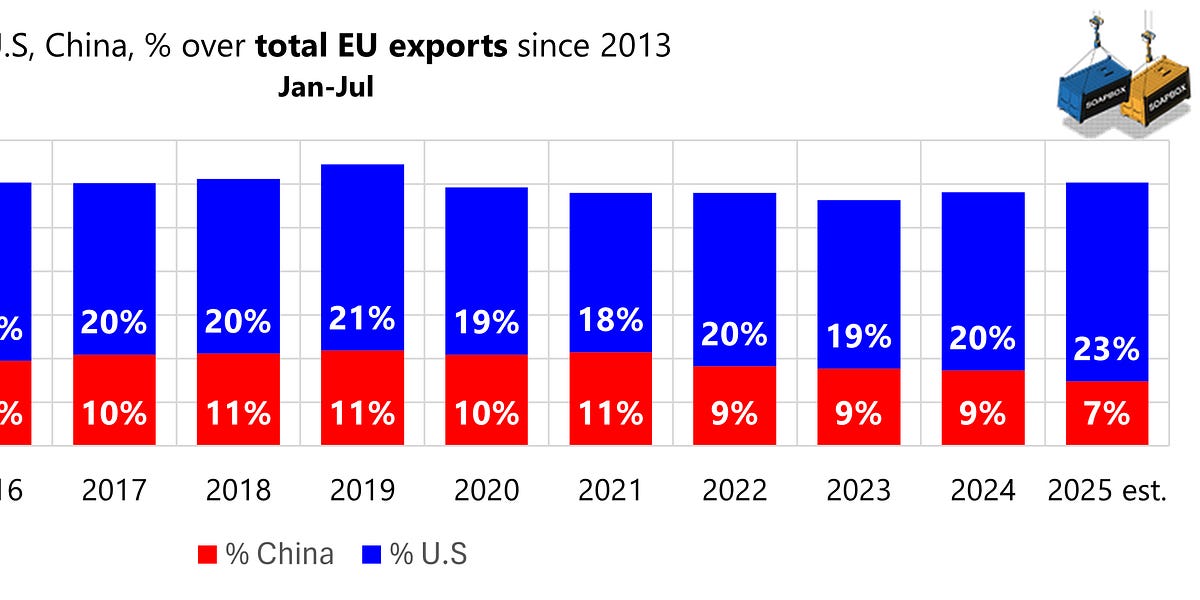

China will not change, and neither will its habit of squeezing foreign firms out with import substitution. EU exports tell the tale: once close to 11% of the total, they are sliding toward 7%, while the U.S. climbs to 23%. Our export future is clearly westward and outward, not eastward.

Some niches in China will stay profitable — luxury, chemicals — but the broad growth story is over. The irony is that the loudest voices in Brussels are not exporters at all, but large European companies with plants in China serving the local market. Their interests are understandable, yet they do not represent Europe’s trade future.

“A significant number of our members are in China for the Chinese market”

Jens Eskelund, EUCCC Chairman

EU policy should follow the real flow of exports, into the U.S. and new emerging markets while keeping a pragmatic channel with Beijing. The risk is letting China-based corporates dominate the debate and distract us from where demand is actually growing. After all, the containers are already heading west.

On September 5, 2025, China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM)’s Trade Remedy and Investigation Bureau announced a preliminary finding that certain pork and pig by-products imported from the EU are being dumped in China and are causing substantial injury to Chinese domestic producers. As a result, starting from September 10, 2025, importers must pay a cash deposit (guarantee) at Customs, calculated based on each exporter’s specific dumping margin and applied to the CIF value of the goods.

With the exception of the period when China was hit by ASF, EU exports of swine offal have consistently exceeded pork meat exports in volume

With the exception of the period when China was hit by ASF, EU exports of swine offal have consistently exceeded pork meat exports in volume

The anti-dumping duties cover a wide range of products, including fresh, chilled, frozen, and processed pork and by-products such as intestines, bladders, and fats. Importers are required to pay the deposit plus applicable VAT, calculated as: Deposit = (Customs-assessed CIF value × Company’s deposit rate) × (1 + VAT rate).

That’s China being China

Source: Trade Remedy Bureau

If we understand well, the EU–Mercosur pact is more than a trade deal: it is a mixed agreement that also covers political and cooperation chapters. Normally this would mean two steps: consent from the European Parliament and then ratification by all 27 member states, where a single “no” could block it.

To avoid this, Brussels could decide to split the deal. In that case, the trade pillar alone would fall under EU exclusive competence and could take effect provisionally if Parliament approves.

A vote could still happen in 2025 but perhaps it will slip into 2026.

As SOAPBOX reported on Aug. 18, in the first half of 2025 China–EU rail trade is fading and stunningly one-sided: for every six containers from China, only one goes back

China will not change, and neither will its intention to be the permanent EU’s dominant supplier. EU imports tell the story: goods from China have grown from 16% of total imports in 2013 to 22% today, while the U.S. has stagnated around 11–14%. Europe is more dependent on Chinese products than ever, from electronics to machinery to consumer goods.

Some dependence is unavoidable, but the structural imbalance is clear. The irony is that while EU exports are shifting toward the U.S., EU imports remain heavily tilted toward China. This leaves Brussels vulnerable to shocks, coercion, and overcapacity floods in sectors like EVs, batteries, and solar panels or daily consumer goods.

The loudest voices in Brussels are often the same corporates that rely on Chinese supply chains. Their interests are understandable, yet they do not represent Europe’s strategic resilience. EU policy should follow the real flow of risk, away from single-supplier dependency, while keeping a pragmatic channel with Beijing.

The recommendation is straightforward: accelerate diversification of imports, build redundancy in supply chains with India, ASEAN, Mexico, MERCOSUR, and trusted neighbors, and strengthen trade defense instruments against subsidized surges. After all, the containers are still pouring in from the East.

The U.S. once allowed imports under $800 to slip in without tariffs or real customs checks. Chinese online platforms seized the opportunity to flood the American market. That window closed with Trump’s return to power and the tide of cheap goods has shifted toward Europe.

The EU still grants an exemption for parcels under €150, and nearly everything sold by Shein, TEMU, AliExpress and their peers falls below that line. As a result, Europe has suddenly become their top market. The exemption is due to be phased out by March 2028, but for now the flood is on.

Hungary has become a new entry point. Chinese platforms ship on average 340 tons a day there, with volumes in 2025 already up more than 300 percent. Yet scrutiny is catching up: SHEIN was recently hit with a hefty fine for regulatory non-compliance, and France is pressing for the Commission to have the power to delist offending platforms altogether.

For Beijing, this business is simply too profitable to give up. Despite all the official talk of “new productive forces,” China’s number one export reality is the same as ever: cheap stuff.

In 2025, cross-border e-commerce exports are on track to hit a stunning $128 billion. Cheap China is back.

China’s aggressive purchasing of copper scrap is creating serious supply shortages for European smelters, especially in Germany.

China’s propaganda hails the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) as a club of Eurasia’s great powers. Trade tells a different story: the bloc is commercially subservient to China.

In 2024, for every dollar these nine members export to China, they end up importing three dollars back. China’s net gain through trade with its SCO partners is 31% a sign of the bloc’s self-delusion.

In some cases the imbalance is staggering: China runs a surplus equal to 82% of its total trade with Tajikistan, 75% with Kyrgyzstan, and nearly 60% with the recent entrant Belarus.

Overall, Beijing siphons off the equivalent of about 2 % of the SCO’s combined GDP each year. Not a bad business, is it?

But wait, by our forecast, China’s surplus with the SCO bloc will rise by nearly 6 percent in 2025.

While the propaganda feeds Eurasian pride, Beijing’s profit will grow by another 10 billion dollars.

The only Central Asian country outside the SCO is Turkmenistan, which attends SCO as an observer. It enjoys an ample $9 billion trade surplus with China by shipping just one product: natural gas.

With the exception of a brief uptick after the lifting of Covid restrictions, China’s PMI employment subindex has remained in contraction for more than three years.

So far in 2025, China has nearly doubled its imports from Israel, driven by a 180% surge in chip purchases. Processor and controller imports alone tripled in the first seven months, even as Intel was downsizing its Kiryat Gat facility. The spike likely reflects stock releases rather than fresh output, with Chinese buyers pivoting hard into Intel processors and controllers that remain licensable.

Any observer will notice that for Beijing, securing semiconductors matters more than political consistency, given China’s stance on Israel and Gaza. It is also worth recalling that China’s regulator, SAMR, never gave its consent to Intel’s attempted acquisition of Israeli chipmaker Tower.

We are committed to sharing with you the best trade analysis we have to offer.

If you would like to share something with us, feel free to comment in the section below or drop us a line at [email protected]

Like this:

Like Loading…

Разгледайте нашите предложения за Български трактори

Иберете от тук

Българо-китайска търговско-промишлена палата